Elena Miceli, ’20

Lorca on Motherhood: A Societal Ordinance, Not One’s Life Calling

Elena Miceli was a Spanish major, Italian minor at Holy Cross. After graduating, she spent two years teaching English in Barcelona and Madrid, Spain. Currently a freelance writer who focuses on the topics of Italian and Spanish culture, art, and travel, she plans to pursue an MFA in Creative Writing abroad. The following piece was first published on the European arts and culture website Arcadia (www.byarcadia.org) and appears here by the author’s permission.

“A woman’s place is in the kitchen” may be a running joke in 2023, but in Spain in the 1930s, the statement would have been met with stern nods of approval. Spanish playwright, author, and poet Federico García Lorca demonstrates just how deep-rooted this sentiment was in Spain through his rural tragedies that offer the rare perspective of almost exclusively female characters. His 1934 play Yerma follows the life of a young woman, Yerma, and her desperate desire to procreate in a society that decrees this as a female’s rightful and only role in the world. Her name, literally meaning “barren” and “wasteland” in Spanish, leaves nothing to the imagination as to what the central theme is throughout the play. While Lorca leaves his characters’ roles unfulfilled, he fulfills his own self-appointed role as a writer of tragedy through the harsh realities of the thirties, when one need not look further than the life of a woman to discover tragedy. His final work, La casa de Bernarda Alba, was written in 1936, finished just before the playwright’s untimely death by execution that same year. The play observes the household of the matriarch (and oftentimes, patriarch), Bernarda Alba, and her five bitter and outspoken daughters. The women suffer isolation and are denied any autonomy under the watchful eye of their authoritarian mother, which drives them to lethal extremes when an escape route through marriage is introduced to the brooding bunch.

Any work of literature is a reflection of the society in which it was written, holding a mirror up that, oftentimes, exposes ugly realities that have been masquerading as culturally acceptable norms. These two famous plays, which simply paint a picture of daily life in rural communities, are categorized as tragedies not because of the corporeal deaths that take place, but because of the hypothetical deaths of the lives Lorca’s characters could have experienced if not for the uncompromising gender roles of society.

The rural backdrop of 1930s Spain seems like it might be the very birthplace of the well-known proverb “It takes a village to raise a child.” After all, during this period, “woman” was synonymous with “mother.” Yerma’s tribulations extend beyond her inability to fulfill a role as a woman. It corrodes her very gender identity, going as far as to say “If only I were a woman” (Lorca, 1934), implying that because she is not a mother, she is not even a real woman. Since the occupation of Mother was such a vital title, if one found themself “unemployed,” wouldn’t they welcome any child against their barren bosom? Why would that role be limited to being a mother solely to the fruit of one’s loins? However, Spanish women’s desperation for offspring draws a firm and unwavering red line between “my children” and “others’ children.” When Yerma’s husband, Juan, attempts to quiet his wife’s unceasing implorations for a child by suggesting one of her nephews live with them, Yerma quips with a biting “I don’t want to look after other people’s children. I think my arms would freeze from holding them.” (Lorca, 1934). This is not the forlorn voice of a woman yearning to love a child, this is the bitter voice of a woman who is failing to fulfill a societal role which she knows will result in suffering the ire of the masses. She is painfully aware that her life will be reduced to anecdotal jabs that help the townswomen pass the time as they launder the clothes belonging to their own societal success and bask in their good fortune.

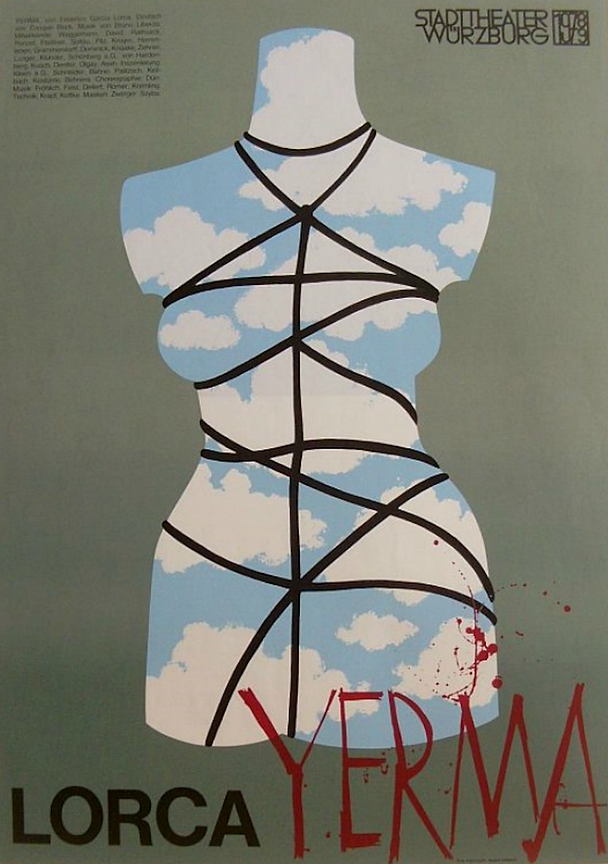

![Figure 1: "Yerma" Poster (M Palitzsch, 1978).]()

![Figure 2: Painting of "Yerma", Theatre Catalogue (Vernazza, 1977).]()

![Figure 3: "Vacía pero en flor" ("Empty but in Bloom"). Drawing of Yerma (Arrieta, 2016).]()

Juan’s solution of adoption is the natural remedy for a person who wishes to be a parent for the sole purpose of being a parent. However, it is clear by Yerma’s acrimony to this suggestion that she does not wish to be a parent; she wishes to abide by the rules that society dictates. The penultimate scene of the play offers Yerma an alternative route to motherhood, but one that is stained with shame and sin. An old woman offers refuge to Yerma as her potential daughter-in-law, offering up her allegedly virile son to fill her empty womb. Yerma repudiates the old woman’s offer with disgusted verve, launching into a tirade about honor and loyalty. To someone living outside of the stringent cultural regulations of 1930s Spain, this reaction may seem a little harsh. If it were truly about a child and a child alone, this seems like an unfortunate yet viable resolution. Yerma is not staying in her marriage out of love, as it was verbally established in no uncertain terms that she has no love for Juan. She stays because she has accepted her fate as a barren woman, but refuses to accept a fate of being doubly shamed as both barren and a

“floozy” who has abandoned her vows of virtue and matrimony. Society has bound her to this man, and Yerma, a steadfast disciple of society to the point of cultural personification, refuses to stray (Devi & Selvalakshmi, 2018).

In the crescendo of the final scene, Juan admits that he does not desire a child, and asks Yerma to relinquish these hopes. “Many women would be happy to live your life. Life is sweeter without children. I’m happy without them. It’s not your fault” (Lorca, 1934). During a time when women were blamed and shamed for barrenness, Juan’s acquittal of Yerma’s “deficiency” is frankly shocking. He proclaims that all he wants is Yerma and Yerma alone, not what she can provide for him. He is exonerating her from a backbreaking life devoted to the nonstop care of children and allowing her to dodge the danger of childbirth, a very real risk in rural areas nearly a century ago. For example, in La casa de Bernarda Alba, La Poncia makes an alarmingly nonchalant comment that from “her experience” Angustias will die in childbirth from her first child due to her narrow hips (Lorca, 1936). Yerma's husband is offering her the chance to escape such a fate, yet society has told her that being a childless wife is a fate worse than death. Juan’s candor proves to be his demise, as it prompts Yerma to choke him to death. After which she screams “I’ve murdered my child! I’ve killed my own son!” (Lorca, 1934). Any scant hope of ever fulfilling her societal role dies with her husband; she has destroyed the only culturally acceptable route to conceive a child.

![Figure 4: Scene with Yerma choking Juan (Iberfoto / Bridgeman Images, 1960).]()

“No Man is an Island,” But Every Woman May Be

Yerma’s literary foil appears in the form of a nineteen-year-old married girl who is child-free. In this case, the positive adjective of “child-free,” is a more apt description than the negative form of “childless,” which can be applied to Yerma. This girl spurns the idea of motherhood and is gleeful to have escaped it thus far, despite her marital status. Lorca grants her the character title of “second girl,” not “second woman,” because by Yerma’s definition, her lack of offspring does not make her a woman. When the girl voices her revolutionary ideas of living life free from burden, a mystified Yerma asks why she even got married. The girl is not at a loss for words:

These impassioned sentiments sound more like the musings of a 2023 independent single woman living alone in a New York City townhouse with her name on the mortgage than that of a 1934 married girl living in a rural Spanish village with her name on nothing, not even her own womb. This novel thinking is why she has been labeled as “crazy,” by the other townspeople with whom she has shared these beliefs. Through the eyes of society, the girl is rejecting her one and only job, and since she rebuffs the title of “mother,” her new title is “crazy.” The girl is anticipating Yerma’s scandalized rebuke, yet it does not come. She simply steamrolls over the girl’s speech, writing it off as so radical it need not even be properly admonished aside from a flippant “hush.” Yet, one of the points in the girl’s senseless rambling resonates with Yerma. She mentioned that her mother had herbs to aid with reproduction, and Yerma inquires as to the woman’s whereabouts, a question filled with transparent ulterior motives. Even when confronted with the notion that life without children does not have to be marked by misery and failure, but instead by joy and liberation, Yerma is not deterred. Her societal acquiescence is an indelible part of her character.

The juxtaposition of the girl and Yerma does not stop at their conflicting opinions on motherhood, but their perspective on society. The girl’s ideals on how a woman’s quotidian life could and should be led are so resolute that they have created an impermeable shield against the harsh maelstrom of society’s dictations. She literally laughs in the face of Spanish society’s pressure to reproduce and refutes the label of “crazy.” Her own validation is all she needs. Meanwhile, Yerma is floundering in the storm, caught out with no umbrella and no refuge in sight except the safe and dry ivory tower in the distance, reserved exclusively for the village mothers who look down on her with pity and secret schadenfreude.

La casa de Bernarda Alba: Where Blood Is Not Thicker Than Water

Although La casa de Bernarda Alba’s focus is not primarily on the societal role of becoming a mother, that does not mean that the maternal opinions of Bernarda’s daughters do not seep into the crevices of conversation. While the daughters are discussing the eldest, Angustias’s, impending nuptials, La Poncia comments that if she starts having children, the daughters will have to sew clothes for their nieces and nephews. This notion is met with revulsion, as Magdalena “has no intention of sewing a stitch,” and Amelia latches onto the aversion with: “Much less look after someone else’s children. Look at the neighbors down the street, martyrs to four little idiots” (Lorca, 1936). There is not an ounce of ambivalence in the women’s statements; any children of their sisters will be getting nothing from their aunts except animosity. They share the same stance on other people’s children as Yerma; it is no matter if their familial blood runs through their veins, if a child is not fully their own then they certainly will not be participating in raising any child in the proverbial “village.” Their mother declared that the mourning period for their recently deceased father will be eight interminable years where not even a breeze will enter the house. Despite this ennui, Magdalena refuses to help lighten the burden of a hypothetical new mother who is not a stranger but her own sister.

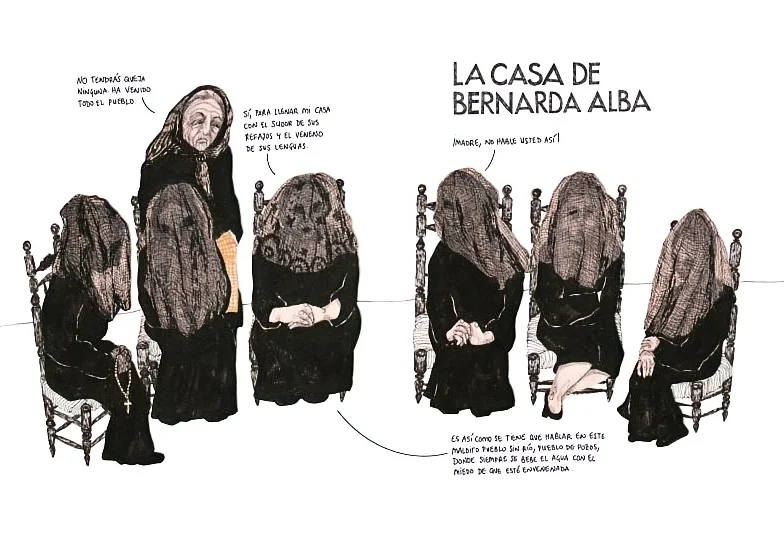

![Figure 5: "La Casa de Bernarda Alba" Poster (Mancini, 2016).]()

![Figure 6: "Casa #3" from the Bernarda Alba Series (Carazo, 1990).]()

Amelia refers to the parents of the four children down the street as “martyrs,” a title that requires the invoked person to be dead. Thus, Amelia is equating motherhood to death. Calling the children themselves “idiots” demonstrates a reproach of motherhood that goes far deeper than other people’s children. It seems that Amelia is questioning the very fabric of the female role as a mother. The brazen outspokenness on delicate topics that the sisters constantly partake in is ironic, as one of Bernarda’s reasons behind the abject isolation she subjects her daughters to is presumably to shield them from the outside world and its ways of warping pure and innocent girls. In the world that these women live in, a female’s greatest and only strength is her innocence and pristine reputation. However, through direct attacks on society such as the aforementioned viewpoint, it appears that the opposite has occurred. The isolation that can rival a “convent,” as La Poncia called the household, has given the women ample time to construct their own ideas and perspectives on socially-accepted roles. The sisters, especially young Adela, view their internment at La cárcel de Bernarda Alba as punishment, yet it has fostered a rare environment where one can freely express one’s opinions, a foreign concept for women in the 1930s. In fact, the play was written in 1936 but was banned in Spain until 1963 “partly because the behavior and language of the characters was regarded as shockingly immoral” (Orwin, 2017).

There is a natural conflict between mothers and daughters that does not exist between mothers and sons, and this phenomenon is only amplified when the mother-daughter ratio is 1:5. Psychoanalytical theories shed light onto the tense and complex relationship between Bernarda and her daughters. According to American sociologist Nancy Chodorow, “conflict arises because mothers ‘are the same gender as their daughters and have been girls, mothers of daughters tend not to experience these infant daughters as separate from them in the same way as do mothers of infant sons’”(Gabriele, 1993). Despite the fact that the women’s mother-mandated quarantine from the outside world has embittered them, Bernarda’s refusal to marry off her daughters is not out of spite. Based on Chodorow’s assertion, Bernarda sees herself and her five daughters as one entity. She has already lived through each one of the ages her daughters are at, and has the advantage of knowledge and experience drawn from retrospect that they lack. She makes her opinion on marriage known when La Poncia gently criticizes her for her daughters’ lack of suitors. “To sell them off!” Bernarda erupts with anger at the suggestion of marriage (Lorca, 1936). This singular statement is all that is needed to ascertain Bernarda’s stance on marriage. The usage of the verb “sell” does not require further elaboration. Marriage is to women what cattle auctions are to livestock. When Bernarda’s first husband died, who is thirty-nine-year-old Angustias’ father, there was the same mandatory eight-year mourning period that the women are observing in the play for Bernarda’s second husband. Eight years of mourning plus the human gestation period of nine months equals almost exactly nine years, which is the age gap between Angustias and her half-sister Magdalena. Taking this into consideration, Bernarda was married off to her second husband less than three months after the end of the mourning period of her first. During this second marriage, she gave birth to four daughters in the span of ten years. Since she views her daughters as extensions of herself, by denying her daughters’ marriages she is reflecting upon her own girlhood and what she would have wanted; a private and peaceful life with her family, hidden from the prying eyes of society and its expectations.

![]()

Figure 7: Illustration from the book Federico (Ros, 2021).

︎

The Female Experience Meets the Lorquian Experience

It is easy to invalidate a man’s literary commentary on the female experience. Written by someone who has not experienced something firsthand, any account of the actions and emotions of an event is bound to be exaggerated and overdramatized, or contrived and minimized. The tried-and-true advice to “write what you know,” is credible for a reason. What does a man know about what it is to be a woman? However, Lorca abided by this rule to a far higher degree than superficially thought. He grew up in Fuente Vaqueros, a small village in Granada. Like Yerma and La casa de Bernarda Alba, many of his dramas were “rural tragedies” which took place in the countryside of which he was familiar, with characters laboring under the strict traditional institutions he grew up witnessing (Montes, 2023). Despite Lorca’s realistic penning of rural communities where the female is the ama de casa while the male works the fields, he himself did not perpetuate the cultural roles of his hometown. Unlike the farmers in his stories, Lorca was not resigned to toil in the fields to make a living due to his family’s wealth, which acted as a soft cushion between him and labor that “permitted him to live an absolutely free life, dedicated solely to the imaginings of fantasy or poetry” (Salinas, 1972). A man absolved of fulfilling a cultural role, Lorca moved to Madrid at twenty-one. It was a city geographically close to Granada but might as well be another world away. The metropolis fostered the creativity he demonstrated from a young age and he quickly “conquered” Madrid, in the words of his good friend and fellow Spanish poet Pedro Salinas (Salinas, 1972). In 1972, Salinas spoke warmly of his deceased friend in a speech prefacing the reading of a compilation of Lorca’s poems at Johns Hopkins University:

![]()

Figure 8: Photo of Federico García Lorca (Stainton, 1919).

Unfortunately, Salinas was erroneous in declaring that Spaniards esteem an individual based on “how he is.” A suspected homosexual, Lorca faced prejudice and bigotry from the deeply homophobic Spanish society of the early twentieth century. Some found his writing “intensely homoerotic,” which led to the ban on many of his works in 1954 and censorship on some until the end of Franco’s dictatorship –an extremely far-right institution– in 1975 (Montes, 2023). In this way, Lorca shared a bond with the plight of women that elucidated his fascination with depicting their role in his literature; they were both members of a marginalized community. Feminist protests had been slowly but steadily increasing in Madrid since the 1890s, with an encouraging boost from women joining the workforce in World War One (Johnson, 2008). Lorca’s decision to represent female roles, both traditional and radical, stems from a personal vendetta against a fight he could not win in his lifetime.

Conclusion

To the naked eye, Federico García Lorca was attempting to step into the shoes of women in 1930s rural Spain. Normally, this would be cited as an enormous overstep, especially judging from his lofty position in a financially-stable ivory tower not dissimilar to that of Yerma’s village mothers. However, the events of Lorca's life provided the experience necessary to justify his actions and give a voice to the whisper that was women’s daily struggles. Yerma and La casa de Bernarda Alba’s continual appearance on stage proves that while Lorca’s life was cut short, his work’s messages live on as renditions of history textbooks far more engaging than any dry account ever could.

Bibliographical References

Devi, R. R., & Selvalakshmi, A. (2018). Yerma as a Victim of Social Mores and Code of Honour in Lorca’s Yerma. Language in India, 18 (5). URL: http://www.languageinindia.com/may2018/renukadevicodeofhonoryerma.pdf

John P. Gabriele (1993) Of Mothers and Freedom: Adela's Struggle for Selfhood in La Casa de Bernarda Alba ,Symposium: A Quarterly Journal in Modern Literatures, 47:3, 188-199, DOI: 10.1080/00397709.1993.10113464

García Lorca, Federico. (1936). The House of Bernarda Alba (La casa de Bernarda Alba) A Drama of Women in the Villages of Spain. A. S. Kline (2007). PDF: https://teenvalues.eu/wp-content/uploads/2020/06/La-casa-de-Bernarda-Alba.pdf

García Lorca, Federico. (1934). Yerma. A. S. Kline (2007). PDF:http://uploads.worldlibrary.net/uploads/pdf/20121106214533yermapdf_pdf.pdf

Johnson, R. (2008). Federico García Lorca’s Theater and Spanish Feminism.Anales de La Literatura Española Contemporánea, 33(2), 251–281. URL:http://www.jstor.org/stable/27742554

Montes, L. (2023). The Life and Legacy of Federico García Lorca. Detroit Opera. URL: https://detroitopera.org/the-life-and-legacy-of-federico-garcia-lorca/

Orwin, K. (2017). La casa de Bernarda Alba. The King’s School, Canterbury. URL: https://www.kings-school.co.uk/news/la-casa-de-bernarda-alba/

Salinas, P. (1972). Federico García Lorca. MLN, 87(2), 169–177. DOI:https://doi.org/10.2307/2907729

Visual References

Cover Image: Shotgun Players. (2023). Photo of play "Yerma." Retrieved from: https://patch.com/california/berkeley/shotgun-players-stage-adaptation-federico-garcia-lorcas-yerma

Figure 1: Palitzsch, M. (1978). “Lorca Yerma” Poster of the Stadttheater Würzburg. Retrieved from: http://www.reprosoc.com/blog/2016/12/2/yerma-and-the-tyranny-of-choice

Figure 2: Vernazza, E. (1977). Painting of Yerma, Theatre Solis Catalogue. Retrieved from: http://eduardovernazza.blogspot.com/2015/07/catalogo-e-v-federico-garcia-lorca-yerma.html

Figure 3: Arrieta, N. (2016). “Vacía pero en flor” (“Empty but in Bloom”) [Illustration]. Retrieved from:

https://web.facebook.com/naiaraarrietailustracion/photos/vacía-pero-en-flor-así/1137788269610723/?_rdc=1&_rdr

Figure 4: Iberfoto / Bridgeman Images. (1960). “Les comediens Aurora Bautista et E. Diosdado dans une scene de la pièce ‘Yerma’ du poète et dramaturge espagnol Federico García Lorca.” Teatro Eslava, Madrid. Retrieved from: https://www.bridgemanimages.com/en/noartistknown/les-comediens-aurora-bautista-et-e-diosdado-dans-une-scene-de-la-piece-yerma-du-poete-et-dramaturge/painting/asset/5358963

Figure 5: Mancini, P. (2016). “La Casa de Bernarda Alba” Poster. Retrieved from: https://www.timbre4.com/teatro/168-la-casa-de-bernarda-alba-version-libre.html

Figure 6: Carazo, C. (1990). “Casa #3” from the Bernarda Alba Series [Ink drawing]. Retrieved from: http://www.artecostarica.cr/artistas/carazo-claudio/casa-3-serie-de-bernarda-alba

Figure 7: Ros, I. (2021). Illustration from the book Federico. Retrieved from: https://www.huffingtonpost.es/entry/biografia-ilustrada-federico-garcia-lorca_es_60f93a36e4b07c153fbc8f9d.html

Figure 8: Stainton, L. A. (1919). Federico García Lorca's headshot. Encyclopedia Britannica. Retrieved from:https://www.britannica.com/biography/Federico-Garcia-Lorca

Lorca on Motherhood: A Societal Ordinance, Not One’s Life Calling

Elena Miceli was a Spanish major, Italian minor at Holy Cross. After graduating, she spent two years teaching English in Barcelona and Madrid, Spain. Currently a freelance writer who focuses on the topics of Italian and Spanish culture, art, and travel, she plans to pursue an MFA in Creative Writing abroad. The following piece was first published on the European arts and culture website Arcadia (www.byarcadia.org) and appears here by the author’s permission.

︎

“A woman’s place is in the kitchen” may be a running joke in 2023, but in Spain in the 1930s, the statement would have been met with stern nods of approval. Spanish playwright, author, and poet Federico García Lorca demonstrates just how deep-rooted this sentiment was in Spain through his rural tragedies that offer the rare perspective of almost exclusively female characters. His 1934 play Yerma follows the life of a young woman, Yerma, and her desperate desire to procreate in a society that decrees this as a female’s rightful and only role in the world. Her name, literally meaning “barren” and “wasteland” in Spanish, leaves nothing to the imagination as to what the central theme is throughout the play. While Lorca leaves his characters’ roles unfulfilled, he fulfills his own self-appointed role as a writer of tragedy through the harsh realities of the thirties, when one need not look further than the life of a woman to discover tragedy. His final work, La casa de Bernarda Alba, was written in 1936, finished just before the playwright’s untimely death by execution that same year. The play observes the household of the matriarch (and oftentimes, patriarch), Bernarda Alba, and her five bitter and outspoken daughters. The women suffer isolation and are denied any autonomy under the watchful eye of their authoritarian mother, which drives them to lethal extremes when an escape route through marriage is introduced to the brooding bunch.

Any work of literature is a reflection of the society in which it was written, holding a mirror up that, oftentimes, exposes ugly realities that have been masquerading as culturally acceptable norms. These two famous plays, which simply paint a picture of daily life in rural communities, are categorized as tragedies not because of the corporeal deaths that take place, but because of the hypothetical deaths of the lives Lorca’s characters could have experienced if not for the uncompromising gender roles of society.

The rural backdrop of 1930s Spain seems like it might be the very birthplace of the well-known proverb “It takes a village to raise a child.” After all, during this period, “woman” was synonymous with “mother.” Yerma’s tribulations extend beyond her inability to fulfill a role as a woman. It corrodes her very gender identity, going as far as to say “If only I were a woman” (Lorca, 1934), implying that because she is not a mother, she is not even a real woman. Since the occupation of Mother was such a vital title, if one found themself “unemployed,” wouldn’t they welcome any child against their barren bosom? Why would that role be limited to being a mother solely to the fruit of one’s loins? However, Spanish women’s desperation for offspring draws a firm and unwavering red line between “my children” and “others’ children.” When Yerma’s husband, Juan, attempts to quiet his wife’s unceasing implorations for a child by suggesting one of her nephews live with them, Yerma quips with a biting “I don’t want to look after other people’s children. I think my arms would freeze from holding them.” (Lorca, 1934). This is not the forlorn voice of a woman yearning to love a child, this is the bitter voice of a woman who is failing to fulfill a societal role which she knows will result in suffering the ire of the masses. She is painfully aware that her life will be reduced to anecdotal jabs that help the townswomen pass the time as they launder the clothes belonging to their own societal success and bask in their good fortune.

Juan’s solution of adoption is the natural remedy for a person who wishes to be a parent for the sole purpose of being a parent. However, it is clear by Yerma’s acrimony to this suggestion that she does not wish to be a parent; she wishes to abide by the rules that society dictates. The penultimate scene of the play offers Yerma an alternative route to motherhood, but one that is stained with shame and sin. An old woman offers refuge to Yerma as her potential daughter-in-law, offering up her allegedly virile son to fill her empty womb. Yerma repudiates the old woman’s offer with disgusted verve, launching into a tirade about honor and loyalty. To someone living outside of the stringent cultural regulations of 1930s Spain, this reaction may seem a little harsh. If it were truly about a child and a child alone, this seems like an unfortunate yet viable resolution. Yerma is not staying in her marriage out of love, as it was verbally established in no uncertain terms that she has no love for Juan. She stays because she has accepted her fate as a barren woman, but refuses to accept a fate of being doubly shamed as both barren and a

“floozy” who has abandoned her vows of virtue and matrimony. Society has bound her to this man, and Yerma, a steadfast disciple of society to the point of cultural personification, refuses to stray (Devi & Selvalakshmi, 2018).

In the crescendo of the final scene, Juan admits that he does not desire a child, and asks Yerma to relinquish these hopes. “Many women would be happy to live your life. Life is sweeter without children. I’m happy without them. It’s not your fault” (Lorca, 1934). During a time when women were blamed and shamed for barrenness, Juan’s acquittal of Yerma’s “deficiency” is frankly shocking. He proclaims that all he wants is Yerma and Yerma alone, not what she can provide for him. He is exonerating her from a backbreaking life devoted to the nonstop care of children and allowing her to dodge the danger of childbirth, a very real risk in rural areas nearly a century ago. For example, in La casa de Bernarda Alba, La Poncia makes an alarmingly nonchalant comment that from “her experience” Angustias will die in childbirth from her first child due to her narrow hips (Lorca, 1936). Yerma's husband is offering her the chance to escape such a fate, yet society has told her that being a childless wife is a fate worse than death. Juan’s candor proves to be his demise, as it prompts Yerma to choke him to death. After which she screams “I’ve murdered my child! I’ve killed my own son!” (Lorca, 1934). Any scant hope of ever fulfilling her societal role dies with her husband; she has destroyed the only culturally acceptable route to conceive a child.

Figure 4: Scene with Yerma choking Juan (Iberfoto / Bridgeman Images, 1960).

“No Man is an Island,” But Every Woman May Be

Yerma’s literary foil appears in the form of a nineteen-year-old married girl who is child-free. In this case, the positive adjective of “child-free,” is a more apt description than the negative form of “childless,” which can be applied to Yerma. This girl spurns the idea of motherhood and is gleeful to have escaped it thus far, despite her marital status. Lorca grants her the character title of “second girl,” not “second woman,” because by Yerma’s definition, her lack of offspring does not make her a woman. When the girl voices her revolutionary ideas of living life free from burden, a mystified Yerma asks why she even got married. The girl is not at a loss for words:

“Because they made me marry. They make everyone marry. If it goes on like this, there will only be little girls left. Anyway, in reality you’re married long before you go to church. But the old women fret about these things. I’m nineteen and I hate cooking and cleaning. And now I have to spend the whole day doing what I hate. What for? Why did my husband need to become my husband? We do the same now as before. It’s all old women’s foolishness… You’ll be calling me crazy too. ‘Crazy! Crazy!’ (she laughs) I tell you the one thing I’ve learned in life: everybody’s stuck in their houses doing what they don’t want to do. It’s so much better outside. I go to the stream; I climb up and ring the bells, I take a drink of anisette” (Lorca, 1934).

These impassioned sentiments sound more like the musings of a 2023 independent single woman living alone in a New York City townhouse with her name on the mortgage than that of a 1934 married girl living in a rural Spanish village with her name on nothing, not even her own womb. This novel thinking is why she has been labeled as “crazy,” by the other townspeople with whom she has shared these beliefs. Through the eyes of society, the girl is rejecting her one and only job, and since she rebuffs the title of “mother,” her new title is “crazy.” The girl is anticipating Yerma’s scandalized rebuke, yet it does not come. She simply steamrolls over the girl’s speech, writing it off as so radical it need not even be properly admonished aside from a flippant “hush.” Yet, one of the points in the girl’s senseless rambling resonates with Yerma. She mentioned that her mother had herbs to aid with reproduction, and Yerma inquires as to the woman’s whereabouts, a question filled with transparent ulterior motives. Even when confronted with the notion that life without children does not have to be marked by misery and failure, but instead by joy and liberation, Yerma is not deterred. Her societal acquiescence is an indelible part of her character.

The juxtaposition of the girl and Yerma does not stop at their conflicting opinions on motherhood, but their perspective on society. The girl’s ideals on how a woman’s quotidian life could and should be led are so resolute that they have created an impermeable shield against the harsh maelstrom of society’s dictations. She literally laughs in the face of Spanish society’s pressure to reproduce and refutes the label of “crazy.” Her own validation is all she needs. Meanwhile, Yerma is floundering in the storm, caught out with no umbrella and no refuge in sight except the safe and dry ivory tower in the distance, reserved exclusively for the village mothers who look down on her with pity and secret schadenfreude.

︎

La casa de Bernarda Alba: Where Blood Is Not Thicker Than Water

Although La casa de Bernarda Alba’s focus is not primarily on the societal role of becoming a mother, that does not mean that the maternal opinions of Bernarda’s daughters do not seep into the crevices of conversation. While the daughters are discussing the eldest, Angustias’s, impending nuptials, La Poncia comments that if she starts having children, the daughters will have to sew clothes for their nieces and nephews. This notion is met with revulsion, as Magdalena “has no intention of sewing a stitch,” and Amelia latches onto the aversion with: “Much less look after someone else’s children. Look at the neighbors down the street, martyrs to four little idiots” (Lorca, 1936). There is not an ounce of ambivalence in the women’s statements; any children of their sisters will be getting nothing from their aunts except animosity. They share the same stance on other people’s children as Yerma; it is no matter if their familial blood runs through their veins, if a child is not fully their own then they certainly will not be participating in raising any child in the proverbial “village.” Their mother declared that the mourning period for their recently deceased father will be eight interminable years where not even a breeze will enter the house. Despite this ennui, Magdalena refuses to help lighten the burden of a hypothetical new mother who is not a stranger but her own sister.

Amelia refers to the parents of the four children down the street as “martyrs,” a title that requires the invoked person to be dead. Thus, Amelia is equating motherhood to death. Calling the children themselves “idiots” demonstrates a reproach of motherhood that goes far deeper than other people’s children. It seems that Amelia is questioning the very fabric of the female role as a mother. The brazen outspokenness on delicate topics that the sisters constantly partake in is ironic, as one of Bernarda’s reasons behind the abject isolation she subjects her daughters to is presumably to shield them from the outside world and its ways of warping pure and innocent girls. In the world that these women live in, a female’s greatest and only strength is her innocence and pristine reputation. However, through direct attacks on society such as the aforementioned viewpoint, it appears that the opposite has occurred. The isolation that can rival a “convent,” as La Poncia called the household, has given the women ample time to construct their own ideas and perspectives on socially-accepted roles. The sisters, especially young Adela, view their internment at La cárcel de Bernarda Alba as punishment, yet it has fostered a rare environment where one can freely express one’s opinions, a foreign concept for women in the 1930s. In fact, the play was written in 1936 but was banned in Spain until 1963 “partly because the behavior and language of the characters was regarded as shockingly immoral” (Orwin, 2017).

There is a natural conflict between mothers and daughters that does not exist between mothers and sons, and this phenomenon is only amplified when the mother-daughter ratio is 1:5. Psychoanalytical theories shed light onto the tense and complex relationship between Bernarda and her daughters. According to American sociologist Nancy Chodorow, “conflict arises because mothers ‘are the same gender as their daughters and have been girls, mothers of daughters tend not to experience these infant daughters as separate from them in the same way as do mothers of infant sons’”(Gabriele, 1993). Despite the fact that the women’s mother-mandated quarantine from the outside world has embittered them, Bernarda’s refusal to marry off her daughters is not out of spite. Based on Chodorow’s assertion, Bernarda sees herself and her five daughters as one entity. She has already lived through each one of the ages her daughters are at, and has the advantage of knowledge and experience drawn from retrospect that they lack. She makes her opinion on marriage known when La Poncia gently criticizes her for her daughters’ lack of suitors. “To sell them off!” Bernarda erupts with anger at the suggestion of marriage (Lorca, 1936). This singular statement is all that is needed to ascertain Bernarda’s stance on marriage. The usage of the verb “sell” does not require further elaboration. Marriage is to women what cattle auctions are to livestock. When Bernarda’s first husband died, who is thirty-nine-year-old Angustias’ father, there was the same mandatory eight-year mourning period that the women are observing in the play for Bernarda’s second husband. Eight years of mourning plus the human gestation period of nine months equals almost exactly nine years, which is the age gap between Angustias and her half-sister Magdalena. Taking this into consideration, Bernarda was married off to her second husband less than three months after the end of the mourning period of her first. During this second marriage, she gave birth to four daughters in the span of ten years. Since she views her daughters as extensions of herself, by denying her daughters’ marriages she is reflecting upon her own girlhood and what she would have wanted; a private and peaceful life with her family, hidden from the prying eyes of society and its expectations.

Figure 7: Illustration from the book Federico (Ros, 2021).

︎

The Female Experience Meets the Lorquian Experience

It is easy to invalidate a man’s literary commentary on the female experience. Written by someone who has not experienced something firsthand, any account of the actions and emotions of an event is bound to be exaggerated and overdramatized, or contrived and minimized. The tried-and-true advice to “write what you know,” is credible for a reason. What does a man know about what it is to be a woman? However, Lorca abided by this rule to a far higher degree than superficially thought. He grew up in Fuente Vaqueros, a small village in Granada. Like Yerma and La casa de Bernarda Alba, many of his dramas were “rural tragedies” which took place in the countryside of which he was familiar, with characters laboring under the strict traditional institutions he grew up witnessing (Montes, 2023). Despite Lorca’s realistic penning of rural communities where the female is the ama de casa while the male works the fields, he himself did not perpetuate the cultural roles of his hometown. Unlike the farmers in his stories, Lorca was not resigned to toil in the fields to make a living due to his family’s wealth, which acted as a soft cushion between him and labor that “permitted him to live an absolutely free life, dedicated solely to the imaginings of fantasy or poetry” (Salinas, 1972). A man absolved of fulfilling a cultural role, Lorca moved to Madrid at twenty-one. It was a city geographically close to Granada but might as well be another world away. The metropolis fostered the creativity he demonstrated from a young age and he quickly “conquered” Madrid, in the words of his good friend and fellow Spanish poet Pedro Salinas (Salinas, 1972). In 1972, Salinas spoke warmly of his deceased friend in a speech prefacing the reading of a compilation of Lorca’s poems at Johns Hopkins University:

“Nothing or no one could resist that vivacity, that laugh and the charm that emanated from [Lorca’s] presence and his conversation. You know that we Spaniards are very sensitive to the exterior expression of a person. We don’t esteem a person solely for what he does and what he is worth, but above all for what he is and how he is, for his charm, his sympathy and friendly feeling, and for his originality” (Salinas, 1972).

Figure 8: Photo of Federico García Lorca (Stainton, 1919).

Unfortunately, Salinas was erroneous in declaring that Spaniards esteem an individual based on “how he is.” A suspected homosexual, Lorca faced prejudice and bigotry from the deeply homophobic Spanish society of the early twentieth century. Some found his writing “intensely homoerotic,” which led to the ban on many of his works in 1954 and censorship on some until the end of Franco’s dictatorship –an extremely far-right institution– in 1975 (Montes, 2023). In this way, Lorca shared a bond with the plight of women that elucidated his fascination with depicting their role in his literature; they were both members of a marginalized community. Feminist protests had been slowly but steadily increasing in Madrid since the 1890s, with an encouraging boost from women joining the workforce in World War One (Johnson, 2008). Lorca’s decision to represent female roles, both traditional and radical, stems from a personal vendetta against a fight he could not win in his lifetime.

︎

Conclusion

To the naked eye, Federico García Lorca was attempting to step into the shoes of women in 1930s rural Spain. Normally, this would be cited as an enormous overstep, especially judging from his lofty position in a financially-stable ivory tower not dissimilar to that of Yerma’s village mothers. However, the events of Lorca's life provided the experience necessary to justify his actions and give a voice to the whisper that was women’s daily struggles. Yerma and La casa de Bernarda Alba’s continual appearance on stage proves that while Lorca’s life was cut short, his work’s messages live on as renditions of history textbooks far more engaging than any dry account ever could.

︎

Bibliographical References

Devi, R. R., & Selvalakshmi, A. (2018). Yerma as a Victim of Social Mores and Code of Honour in Lorca’s Yerma. Language in India, 18 (5). URL: http://www.languageinindia.com/may2018/renukadevicodeofhonoryerma.pdf

John P. Gabriele (1993) Of Mothers and Freedom: Adela's Struggle for Selfhood in La Casa de Bernarda Alba ,Symposium: A Quarterly Journal in Modern Literatures, 47:3, 188-199, DOI: 10.1080/00397709.1993.10113464

García Lorca, Federico. (1936). The House of Bernarda Alba (La casa de Bernarda Alba) A Drama of Women in the Villages of Spain. A. S. Kline (2007). PDF: https://teenvalues.eu/wp-content/uploads/2020/06/La-casa-de-Bernarda-Alba.pdf

García Lorca, Federico. (1934). Yerma. A. S. Kline (2007). PDF:http://uploads.worldlibrary.net/uploads/pdf/20121106214533yermapdf_pdf.pdf

Johnson, R. (2008). Federico García Lorca’s Theater and Spanish Feminism.Anales de La Literatura Española Contemporánea, 33(2), 251–281. URL:http://www.jstor.org/stable/27742554

Montes, L. (2023). The Life and Legacy of Federico García Lorca. Detroit Opera. URL: https://detroitopera.org/the-life-and-legacy-of-federico-garcia-lorca/

Orwin, K. (2017). La casa de Bernarda Alba. The King’s School, Canterbury. URL: https://www.kings-school.co.uk/news/la-casa-de-bernarda-alba/

Salinas, P. (1972). Federico García Lorca. MLN, 87(2), 169–177. DOI:https://doi.org/10.2307/2907729

Visual References

Cover Image: Shotgun Players. (2023). Photo of play "Yerma." Retrieved from: https://patch.com/california/berkeley/shotgun-players-stage-adaptation-federico-garcia-lorcas-yerma

Figure 1: Palitzsch, M. (1978). “Lorca Yerma” Poster of the Stadttheater Würzburg. Retrieved from: http://www.reprosoc.com/blog/2016/12/2/yerma-and-the-tyranny-of-choice

Figure 2: Vernazza, E. (1977). Painting of Yerma, Theatre Solis Catalogue. Retrieved from: http://eduardovernazza.blogspot.com/2015/07/catalogo-e-v-federico-garcia-lorca-yerma.html

Figure 3: Arrieta, N. (2016). “Vacía pero en flor” (“Empty but in Bloom”) [Illustration]. Retrieved from:

https://web.facebook.com/naiaraarrietailustracion/photos/vacía-pero-en-flor-así/1137788269610723/?_rdc=1&_rdr

Figure 4: Iberfoto / Bridgeman Images. (1960). “Les comediens Aurora Bautista et E. Diosdado dans une scene de la pièce ‘Yerma’ du poète et dramaturge espagnol Federico García Lorca.” Teatro Eslava, Madrid. Retrieved from: https://www.bridgemanimages.com/en/noartistknown/les-comediens-aurora-bautista-et-e-diosdado-dans-une-scene-de-la-piece-yerma-du-poete-et-dramaturge/painting/asset/5358963

Figure 5: Mancini, P. (2016). “La Casa de Bernarda Alba” Poster. Retrieved from: https://www.timbre4.com/teatro/168-la-casa-de-bernarda-alba-version-libre.html

Figure 6: Carazo, C. (1990). “Casa #3” from the Bernarda Alba Series [Ink drawing]. Retrieved from: http://www.artecostarica.cr/artistas/carazo-claudio/casa-3-serie-de-bernarda-alba

Figure 7: Ros, I. (2021). Illustration from the book Federico. Retrieved from: https://www.huffingtonpost.es/entry/biografia-ilustrada-federico-garcia-lorca_es_60f93a36e4b07c153fbc8f9d.html

Figure 8: Stainton, L. A. (1919). Federico García Lorca's headshot. Encyclopedia Britannica. Retrieved from:https://www.britannica.com/biography/Federico-Garcia-Lorca